A Hope to Prolong Fertility: Ovarian Transplants

By Tiffany Sharples, Time.com

For Stephanie Yarber, who received a diagnosis of premature ovarian failure at age 14, conceiving children the old-fashioned way was a life’s wish. In 2003, after several unsuccessful — and costly — courses of in vitro fertilization (IVF) using her identical-twin sister’s donated eggs, Yarber began looking into other options. There was adoption, of course. But there was also a riskier experimental alternative: ovarian transplantation.

In her research, Yarber came across a surgeon and fertility specialist in Missouri, Dr. Sherman Silber of the Infertility Center of St. Louis, who in the late 1970s had performed the first successful testicular transplant between male identical twins, allowing the once infertile brother to father five children. Yarber wondered if the same doctor could do a similar procedure between her and her sister. Yarber’s sister, who had three daughters and didn’t plan to have any more children, eagerly agreed to help. “She wouldn’t have said no,” Yarber says. “I knew that.” (See the top 10 medical breakthroughs of the past year.)

Silber remembers the day he first spoke to Yarber. Her enthusiasm was contagious. But despite his vast experience with microsurgery and his success with male patients (he had also performed the world’s first vasectomy reversal), Silber knew that all previous ovarian transplants in the U.S. had failed, as had those performed abroad. Still, he thought, in theory the procedure was possible. Yarber’s surgery was scheduled for April 2004.

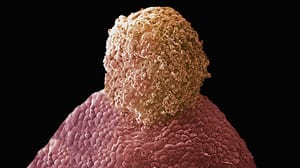

Yarber’s microsurgical procedure involved the transplantation from her sister to her of a thin strip of cortical tissue — the part of the ovary that produces eggs. (The leftover strips of egg-producing tissue from the harvested ovary were frozen and stored for future use.) Within months, Yarber began menstruating. In September 2004, just five months after the transplant, she was pregnant. Five years and another tissue transplant later, Yarber has two daughters, ages 3½ years and 10 months, and is trying for a third child. Owing in large part to Yarber’s willingness to talk about her experience, Silber has since performed the same procedure for eight other sets of identical twins. “There are lots of women who are in our position who are not able to have children and who are looking for something,” says Yarber. “If we didn’t speak about it, there wouldn’t have been so many other twins able to do it.”

The battle to preserve and prolong women’s fertility has become increasingly visible of late. While advances in techniques like cryopreservation (the freezing and storing of eggs and embryos, for example, and now also ovarian tissue for transplants) have increased many women’s chances of pregnancy, IVF is still a time-consuming and expensive process — and one that holds no guarantees. Success rates with IVF parallel fertility rates in the general population, dramatically declining with age. After 40, success rates drop to as low as 23%, and after age 43, Silber says, pregnancy is very rare.

But other fertility treatments — including experimental procedures such as harvesting immature eggs and maturing them in vitro for IVF, and the transplantation of ovarian tissue or entire intact ovaries [news video] — have gained ground in the past five years, especially for women with premature infertility or infertility resulting from cancer therapy. An article published in the Feb. 26 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine urges oncologists to consider fertility preservation, including the use of experimental techniques, more routinely with their patients, since as many as 90% of women who undergo full-body radiation become infertile. But even as fertility specialists offer hope for many women who believed they would never bear their own children, ethicists warn that doctors must tread carefully in developing the technology.

Silber, prompted by success with cortical-tissue transplants, decided to try transplanting a whole ovary. He performed the first successful such transplant between a set of 38-year-old identical twins in January 2007. A few months after surgery, the infertile twin got her period for the first time in more than two decades. Less than a year later, she was pregnant. Last November, she gave birth to a healthy baby girl.

With the use of immunosuppressant drugs, the technique could also work between sisters or even strangers. “We know that’s a safe thing to do,” Silber says, citing the many published cases of babies born to women on long-term immunosuppressants. But Silber believes that the major impact of ovarian transplantation is to freeze the ovary of cancer patients prior to their chemotherapy and radiation to preserve their fertility. It can then be thawed and transplanted back after she is cured.

Fertility specialists agree that ovarian transplantation may be vital for patients suffering from life-threatening diseases. “It’s a no-brainer that we should offer this to cancer patients,” says Silber.

Amy Tucker, now a 31-year-old registered nurse, received a Hodgkin’s disease diagnosis a little more than a decade ago. She underwent six months of initial treatment, after which the cancer recurred. Tucker was then scheduled for a bone-marrow transplant, full-body radiation and additional chemotherapy. But a couple of days before her bone-marrow transplant was to take place, a nurse practitioner happened to mention a lecture she had heard given by a local fertility specialist, Dr. Silber. Until then, Tucker had not once considered her fertility or, for that matter, anything else but the cancer treatment at hand.

Tucker subsequently had her right ovary removed and the tissue preserved. In January, a full decade later, she had her own tissue transplanted back into her body. Now, she hopes, she’ll be able to bear her own children. “I haven’t had a period for 10 years,” she says. “But now, oh my God, I might actually be able to get pregnant.”

One reason specialists urge moving toward whole-organ preservation for cancer patients is that it can be done so quickly. Tucker was able to have her ovary removed right away — unlike harvesting eggs, which can take weeks — and that meant she could begin her cancer treatment without delay. It would take another decade for Tucker to start thinking about children or reimplanting the ovarian tissue. “Basically, Dr. Silber had said, ‘It doesn’t matter when you put it back in. It’s the ovary of a 20-year-old,’ ” Tucker says.

That’s what makes the technique potentially appealing for other women — healthy women who simply want to delay pregnancy for lifestyle purposes. “For those who want to have children, they will often say that it is the supreme experience in their life. To deny that, or to provide obstacles when technology allows it, would be a matter of deep concern,” says Gosden. Though he believes that physicians should seriously consider the ethical implications of using ovary transplants liberally to extend fertility, he says much of the debate will be decided by the would-be mothers themselves.

Silber says without hesitation that he would help all women who wish to preserve their fertility this way — as long as patients were fully aware of the potential risks of ovary removal, which might include menopause three years early. “I know there will be people who have big ethical debates about it,” he says. “Women are able to put off childbearing because of these enhanced opportunities in society and often don’t seriously think about having kids until they’re 35 or 40. By then, there’s a 50% chance that they’re infertile,” he says. “Normally, we worry that science is getting way ahead of society,” Silber adds. “But in this respect it is society that has leaped ahead of science.”

See Also: