by Rick Desloge

February 10, 2006

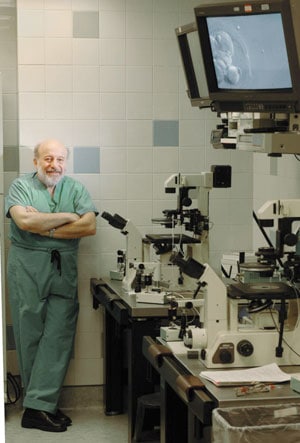

Dr. Sherman Silber’s medical practice, the Infertility Center of St. Louis, has attracted patients from around the world since he started it 25 years ago in conjunction with St. Luke’s Hospital. When he’s here, Silber, 64, puts in 80-hour weeks performing in vitro fertilizations, reversing vasectomies and doing other procedures that help couples who have been unable to conceive children.

When he gets away from it all, he goes far. Silber and his wife, Joan, just returned from a two-and-a-half-week journey to the South Pole [watch video]. Silber and his family — the couple has three grown sons — also spend time at a cabin in Alaska [watch video], where Silber once worked as a rural doctor.

He’s known in his field for the microsurgery procedures he’s developed and the research projects he collaborates on with universities around the world. Silber also is a best-selling author, with nine books to his credit. His best known work, “How to Get Pregnant,” has sold about 400,000 copies.

The pictures on your office walls show an adventure traveler.

The most striking picture on the wall is me at the North Pole in 1986 at midnight. The others are me and my family at our cabin in Alaska [watch video]. The closest city is Anchorage. It’s 200 miles from the nearest road. We have to fly in.

You are a pilot?

I used to fly 30 years ago, then I got to be so busy with my medical practice. Flying is something you have to do as a professional or a serious hobby, otherwise it’s not safe, so I stopped. I was more interested in bush flying, which you do in Alaska.

What brought you to St. Louis?

My wife is from St. Louis. I grew up in Chicago. I never dreamed I was going to move to St. Louis, and I didn’t have any allegiance to Chicago. I grew up in a nasty neighborhood during the ’40s and ’50s. You were never killed, just beaten up. I left when I was 17, after I got a scholarship to the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor. I completed both my undergrad and medical school there. I never really went back home.

What inspired you to write your books?

I had been an English major and was regularly in creative-writing workshops even during medical school. I received a teaching fellowship in the English department while I was in medical school. That’s also how I met my wife, Joan Frager. I was a teaching assistant in her introductory Shakespeare class. I loved her papers. After the semester was over, I had the courage to call her up and ask her out. Two weeks later we were engaged. Since I became deeply entrenched in my practice, everything I write has been medical.

You have a love of primitive cultures. How does that fit in with your work?

I was in Alaska with the public health service for two years — 1967 to 1969 — caring for the native population. That’s where I developed a love of the outdoors and the love of anthropology. Primitive societies tell us more about who we really are, stripped of our outer embellishments. I’ve spent time with the Hadzi bushmen in Africa [watch video], a centuries-old hunter-gatherer culture, and with the Australian Aborigines. When I was with the Hadzi two years ago, I asked them about infertility, and they didn’t understand what I was talking about.

Infertility is a problem of our modern culture?

With few exceptions, infertility is an age-related problem and is seldom found in primitive societies.

You started in medicine as a urologist. What drew you to that field?

When I was with the public health service, we had specialists to help us in every field. But we didn’t have a urologist. I wound up having to study urology and having to wing it as best I could using telephone consults with urologists in Seattle. After the public health service, I went back to Michigan to study urology. I wanted to be a kidney transplanter, and I geared all my urology training for this, including vascular surgery.

How did you go from urology to infertility?

I don’t think we plan our lives as much as we like to think. As part of my training, I developed microsurgery techniques for kidney transplants in rats and wrote a lot of papers about it. That landed me a great job in Melbourne, Australia, and then the University of California at San Francisco in 1974, my first academic job. I wrote a casual paper in October 1975 about a side project, that I thought was minimally important, using this microsurgery technique for reversing vasectomies. After I presented the paper, the next morning I was in the New York Times. The AP picked it up. Walter Cronkite called. That was my first exposure to the media. It changed my career. Nobody knew anything about infertility in those days. I found myself, almost against my will, becoming a fertility expert.

But you stayed with infertility.

Yes, because it was fascinating and a whole new field.

Is that when St. Luke’s called?

I wasn’t recruited. I came calling to see what was available. I visited a few hospitals and was blown away by St. Luke’s. My wife wanted to get back to St. Louis. I was reaching a point where it was administratively difficult to make the progress I wanted to make in a university setting.

Did you get any early encouragement to pursue your medical career?

I’m sure it started at home. My parents were totally dysfunctional and just crazy people. But they did two important things: They gave me undying love, and they kept hounding saying, “You’ve got to be a doctor.”

There must have been other influences?

In medical school I was very insecure about my abilities as a surgeon. You don’t get as much training as you would like. I went to the animal lab at medical school and found Jimmy Crudup [watch video], who was the most inspirational person in my life. Jimmy was a black guy, a truck driver in the south, who came north and got a job as a janitor and would assist in experimental surgeries on the dogs. It took about 10 years for the staff to learn Jimmy was the best surgeon at the University of Michigan, and he didn’t have a high school education. I asked him to take me on as his protégé. We worked together at night during medical school.

Who encouraged your writing?

Donald Hall, and X.J. Kennedy. They were both poets and professors at the university. In 1978, Jacek Galazka, president of Scribners & Sons, took a chance on my first book on infertility. I’d sent more than a dozen letters to other publishers who passed it up.

Are you doing what you thought you would be doing at this age?

Life is a river. When opportunities arise, you have to go for them. But it’s not a straight river. I thought I’d be a vascular heart surgeon. I remember in my urology residency I hated sperm, and here I am.

See Also: